Quaker

Mental Health Care

Reform in America.

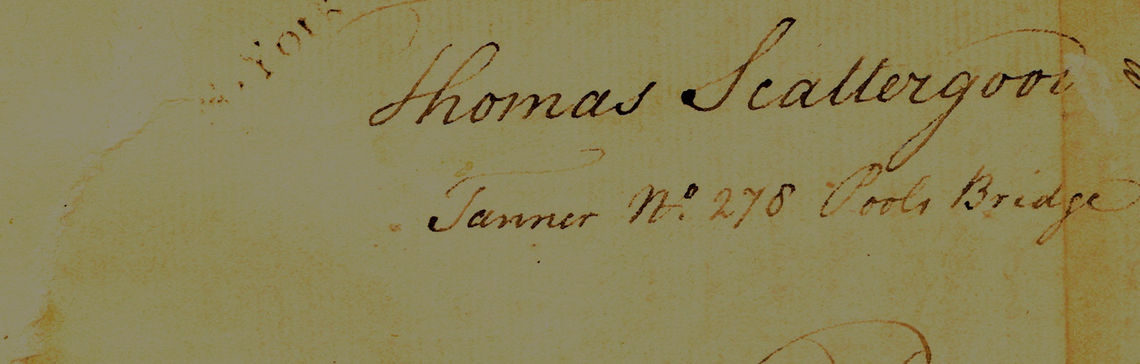

Quaker Minister Pioneers Mental Health Reform in America: Thomas Scattergood (1748–1814)

by David Roby, MD

David Roby, MD, is a neurologist with Einstein Health Care in Philadelphia. He worked at Friends Hospital during the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector, and authored a booklet describing the early experiences of Isaac Bonsall, Friends Hospital's first superintendent. He served on the Board of Managers at Friends Hospital from 1985 to 2006, and is a board member of the Thomas Scattergood Behavioral Health Foundation. Dr. Roby is currently working on a biography of Thomas Scattergood.

I.

Thomas Scattergood was born January 23, 1748 in Burlington, New Jersey. While trained as a tanner, he was drawn to Quaker ministry where he rose to prominence at his local meeting. He had several personal tragedies in his life. His father died when he was only six years old. His first wife died after eight years of marriage. Perhaps his own experiences made him more sensitive to others’ tribulations.

Scattergood himself was prone to sadness and withdrawal and was referred to as the “mournful prophet.” However, he was extremely dedicated to his work as a Quaker minister, and would persevere through God’s presence. In 1794 Scattergood set sail to England, where he would remain for six years. During Scattergood’s lengthy sojourn in English, he would preach, meet with fellow Quakers, visit schools, prisons and orphanages. During the voyage, he writes in his diary:

I have been sitting since dinner, pensively musing and thinking of my family and North meeting… Oh how desolate has been the state of my mind since I parted from my dear wife and family. I could say in humble acknowledgment to the God of my life, that He was my light and my song, my shepherd, and I should not want… Lord, I believe, help Thou my unbelief.

His sympathy with the afflicted was often manifest…claiming his tender regard and bringing to his brethren an account of their suffering, hoping to alleviate their suffering.

Individuals afflicted with mental illness have a long history of being treated with contempt and isolation. Many considered them to be possessed by demons, and deserving of punishment and even death. As late as 1777, London asylums charged visitors to observe patients with mental illness for their amusement or curiosity. By contrast, Quakers view all people as enlightened by the divine, and entitled to respect and consideration. This view of humanity may have sensitized Quakers to the plight of those with mental illness.

II.

In 1791, Hannah Mills, a young Quaker woman, became acutely ill, and displayed mental changes. She was sent to the York Asylum, and her family, who lived some distance from York, asked Quaker friends to visit her at the Asylum. Unfortunately, when they tried to visit, they were turned away, being told she was unfit to receive visitors. Tragically, she died within weeks and several local Quakers from York decried this situation. William Tuke proposed that Quakers create their own institution for those afflicted with mental illness. The situation caused some Quakers to reflect on the situation of the insane. It was felt that there might be some advantage if the Society of Friends created their own institution which could provide milder, more appropriate treatment. It was hoped that if patients enjoyed a lucid interval, they could experience companionship with others of similar beliefs and habits.

Within four years, the York meeting had a plan, had raised funds, and began admitting patients in 1796 to the York Retreat. Three aspects of the Retreat’s early experience deserve mention. First, the retreat promoted the concept of “moral treatment.” Moreover, this emphasized a positive, nurturing, sympathetic attitude towards patients, and a safe, attractive, respectful environment. Second, they found that a surprisingly high number of their patients improved dramatically. This was particularly true if the mental illness was of recent onset. Thirdly, they kept meticulous financial records, and discovered that they could provide kind, compassionate care, and be financially solvent. The Quakers had acquired considerable experience in establishing schools, and obtaining financial support from their members. This fund raising was all the more successful as their cause was embraced and relevant information distributed. So it was that within several years of opening, the York Retreat was regarded locally as a great success. Interested parties came to visit the Retreat and began creating similar institutions.

In 1799, Scattergood traveled to York where he dined with William Tuke, the founder of the York Retreat. He also stayed at the home of Lindley Murray, one of the original supporters of the York Retreat. The following day, Scattergood visited the Retreat where he met with 30 Quaker patients with mental illness. Scattergood writes in his diary: “We sat in quiet, and I had vented a few tears, and was engaged in supplication.”

Scattergood’s visit to the York Retreat occurred near the end of his time in England. While it was to be a seminal event, Scattergood yearned to return to his family in Philadelphia. He writes:

When I view my situation, when I consider the distance I am from my home, how long I have been absent, the afflictions I have passed through…my heart has been sometimes overwhelmed. I hastened to be ready to go home, but here I am yet, as a prisoner in bonds.

Once Scattergood returned to Philadelphia, he became involved with teaching and financial support for a newly created Quaker school in Westtown. Scattergood had a number of anecdotal encounters with troubled souls, including people with severe depression and chronic alcoholism. After meeting such individuals, he would abandon his intended plans and devote hours to counseling them and praying with them. “A friend had tears running from her eyes, and after a time and some conversation, she took courage and told me what sympathy she had felt with me.”

One deeply ingrained tenet of the Quaker faith was strenuous objection to war. This view was articulated by George Fox, the founder of the Quaker movement, as early as 1650. As a result, Quakers were objectors to serving as soldiers in times of war. This held true during the American Revolutionary War. One repercussion of this was resentment of Quakers after the war when they tried to participate in politics or other activities. Some observers have suggested that this exclusion from mainstream trends drove them to innovate internally.

III.

Meanwhile, Samuel Tuke, the grandson of William Tuke, was researching the history and progress of the York Retreat. His Description of the York Retreat would be published in 1813, but Samuel acknowledges sharing much of the information in 1810 with his “American friends.” In February 1811, Scattergood proposed to the Philadelphia Yearly meeting that “means should be devised for the care of such members of our society as may be deprived of the use of their reason.”

Scattergood had been speaking to fellow Quakers about mental illness. These conversations “awaked a tender, sympathetic feeling for the welfare of this afflicted class.”

The meeting designated seven individuals to pursue this proposal. Thomas Scattergood was the first to be named, and the list also included Isaac Bonsall, a local farmer who would serve as the first superintendent of Friends Hospital (1817 – 1823). The influence of the York Retreat’s experience is undeniable. The plans for acquiring land, architecture, staff, and financial support are almost identical to that described in Tuke’s account. In April 1812, the Philadelphia Yearly meeting recorded their plan to:

Create an Asylum, as at the York Retreat, for their insane brethren, which would furnish besides the requisite medical aid, such tender and sympathetic attention, and religious oversight as may sooth their agitated minds and thereby under the divine blessing, facilitate their restoration to the inestimable gift of reason.

Sadly, Thomas Scattergood died of Typhus fever in 1814, three years before Friends Hospital would open. Fellow Quakers were at Scattergood’s death bed and noted:

His vital powers now appear to be fast sinking, and his speedy departure was looked for: but reviving a little he said “I do not expect I am going now”… After some time of silence, and when very near his close, he said with emphasis, “I will lead them, and who will stand?”

In retrospect, the personal disposition of Thomas Scattergood combined with the timing of his visit to the York Retreat were profoundly fortuitous in the founding of Friends Hospital. “To Thomas Scattergood, a minister in the Society of Friends, it is generally believed that we are indebted for the inception of the institution.”

And so it was that his son, Joseph Scattergood, was appointed to be one of the original Managers of Friends Hospital. The main building of Friends Hospital is named after Thomas Scattergood. More recently, the Thomas Scattergood Behavioral Health Foundation was created in 2005 with the mission to advance awareness of behavioral health issues. Lastly, the Scattergood Program for the Applied Ethics of Behavioral Health was created in 2007. This program seeks to promote awareness of ethical dilemmas encountered in clinical practice.

References

Journal of the life and religious labors of Thomas Scattergood, a minister of the gospel in the Society of Friends. Stereotype edition, Philadelphia, 1874, Pages 157, 400-401, 404, 487

Description of the Retreat, an institution near York, for insane persons Of the Society of Friends. Containing an account of its origin and progress, the modes of treatment, and a statement of cases. Samuel Tuke. York, England, 1813. pages 22-23.

Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Minutes, 1811.

Friends Asylum 1813-1913, John C. Winston Company Press, Philadelphia, 1913: page 14.

Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Minutes, April 1812.

Acknowledgment: I wish to recognize the kindness, patience and resourcefulness of the library staff at Haverford College, in the Quaker section. They seem to embrace my mission to understand the background and contributions of Thomas Scattergood.